MB Matheblog # 44

MB Matheblog # 44previous article

index website

MB Matheblog # 44 MB Matheblog # 44 |

blog overview previous article |

main page index website |

|

2025-10-30

The Little Prince Comments are welcome. |

Deutsche Version Deutsche Version |

|

The Little Prince is a famous book by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, see his illustration at the top right.

The Little Prince is standing on a planet. This blog article addresses the following question:

(*) Which shape of the planet exerts the maximum gravitational force on the prince? Where should he stand?

The planet shall have volume \(_~V_~\) and homogeneous density \(_~d_~\).

We position the planet in 3-dimensional \(_~(x,y,z)-\)space. The coordinate origin \(_~(0,0,0)_~\) is chosen for the prince's base. The \(_~z-\)axis is defined by his body axis. We will only accept solutions with the planet surface containing \(_~(0,0,0)_~\) and with the gravitational force in \(_~(0,0,0)_~\) solely acting in \(_~z-\)direction.

According to Newton's law of gravitation, a space point \(_~(x,y,z)_~\) in the planet exerts a vector force to the prince's base in \(_~(0,0,0)_~\) which can be decomposed in the constituent forces in \(_~x-,_{~~}y-_~\) and \(_~z-\)directions. We only look for the force in \(_~z-\)direction. This force is given by \[\textbf{(1)}~~~~f_z=G\cdot d\cdot \frac{z}{(x^2+y^2+z^2)^{~3/2}}\] with the gravitational constant \(~G~\).

Considering the entire planet, the overall gravitational effect on the Little Prince in the \(_~z-\)direction is given by \[\textbf{(2)}~~~~F_z=\int_{V} f_z~dV\]

\(F_{z_~}\) is expressed in the unit \(~m/s^2_~\) (\(m\): meter, \(~s\): seconds) since it refers to gravitational acceleration. This will also become evident further below when determining \(_~F_{z_~}\) numerically.

So our goal is to find the shape of the planet that maximizes \(_~F_{z_~}\) in (2).

The maximum property leads to the conclusion that the planet lies entirely in the positive

\(_~z-\)half-space. A mass point in the negative \(_~z-\)half-space would have \(~f_z\lt 0_~\), see (1). Moving it

into the positive \(_~z-\)half-space would therefore increase \(_~F_{z_~}\) in (2).

Now to the core of the reasoning for the solution of (*). We will show that the effect of (1) on the surface of the planet already contains enough information to solve the problem, provided that \(_~F_{z_~}\) is maximal:

The maximum of \(_~r(z)_~\) is \(~\sqrt{2}\cdot (C/3)^{_~3/4}\) , for \(~z=(C/3)^{_~3/4}\).

The following sketch shows the graph of \(_~r(z)_~\) for \(_~C=1_~\). This is one half of the boundary curve of the planet in a cross-section containing the \(_~z-\)axis. The Little Prince stands in negative \(_~z-\)direction, with his feet at the origin of coordinates.

Note: With the derivation of \(_~r(z)_~\) in (4) and (5), it becomes clear that the planet has no voids.

.png)

Figure 1 \(_~r(z)_~\) for \(_~C=1_~\)

The shape of the curve in figure 1 does not depend on the choice of \(_~C_~\). One can show that any graph of \(_~r(z)_~\) for an arbitrary \(_~C_~\) can be transformed to the graph for \(_~C=1_~\) by uniformly scaling in the \(_~r-_~\) and \(_~z-_~\)directions.

Such a similarity transformation for a function \(_~f(x)_~\) and a scaling factor \(_~1/h_~\) is given by

\[f(x)~~\rightarrow~~\frac{1}{h}~f_~(h\cdot x)\]

Here, we choose \(_~h=C^{3/4}\) :

\[r(z)_{~C}=\sqrt{C\cdot z^{2/3}-z^{2~}}~~~\rightarrow~~~\frac{1}{h}~\sqrt{C\cdot h^{2/3}\cdot z^{2/3}-h^{2~}\cdot z^{2~}}~=~C^{-3/4}\cdot \sqrt{C^{3/2}\cdot z^{2/3}-C^{3/2}\cdot z^2}~=~\sqrt{z^{2/3}-z^{2~}}~=~r(z)_{~C=1}\]

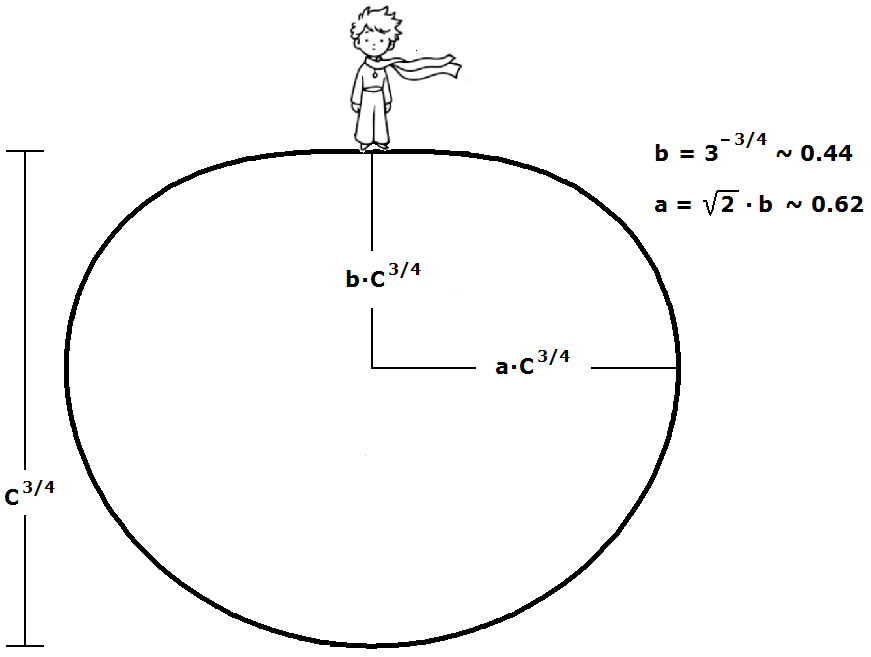

We complete the curve in figure 1, rotate it \(_~90°\) clockwise, and remove the restriction \(_~C=1_~\):

Figure 2 Cross-section of the rotational solid

This planet meets the two conditions we initially set for a valid solution:

The planet touches the prince's feet and the gravitational force acts only along his body axis (due to the rotational \(_~z-\)symmetry of the planet).

Thus, the initial question (*) is answered.

The Little Prince stands at the end of the axis of rotation on the "blunt" side of a rotational solid, as

shown in figure 2. – Next, we will show how \(_~C_~\) depends on \(_~V_~\).

In the calculation of the volume below, we make use of the planet having no voids (see above).

\[V=\int_0^{C^{3/4}}\pi\cdot r^2(z)~dz~=~\pi\int_0^{C^{3/4}}(_~C\cdot z^{2/3}-z^{2_~})~dz~=~\pi~\left[\frac{3~C}{5}~z^{5/3}-\frac{1}{3}z^{3_~}\right]_0^{C^{3/4}}~=~\frac{4_~\pi}{15}~C^{9/4}\]

\[\textbf{(6)}~~~~C=\left(\frac{15_~V}{4_~\pi}\right)^{4/9}\]

With (6) we can evaluate \(_~{F_z}_~\) in terms of \(_~V_~\) and \(_~d_~\). With (1) and (2) we get:

\[F_z~=~G\cdot d\cdot \int_{V} \frac{z}{(x^2+y^2+z^2)^{~3/2}}~dV\]

Using cylinder coordinates yields

\[F_z~=~G\cdot d\cdot \int_{0}^{C^{3/4}}\int_{0}^{\sqrt{Cz^{2/3}-z^2}}\int_{0}^{2_~\pi} \frac{z\cdot r}{(r^2+z^2)^{~3/2}}~d\phi~dr~dz\]

\[~~~~~~=~2\cdot \pi\cdot G\cdot d\cdot \int_{0}^{C^{3/4}} \left[_~-\frac{z}{\sqrt{r^2+z^2}}~\right]_{r~=~0}^{r~=~\sqrt{Cz^{2/3}-z^2}}~dz\]

\[~~~~~~=~2\cdot \pi\cdot G\cdot d\cdot \int_{0}^{C^{3/4}} \left(1-\frac{z^{2/3}}{\sqrt{C}}~\right)~dz\]

\[~~~~~~=~2\cdot \pi\cdot G\cdot d\cdot \left[_~z-\frac{3}{5}\cdot \frac{z^{5/3}}{\sqrt{C}}_~\right]_{0}^{C^{3/4}}~=~\frac{4}{5}\cdot \pi\cdot G\cdot d\cdot C^{3/4}\]

With (6) we arrive at:

\[\textbf{(7)}~~~~F_z=\left(\frac{4_~\pi}{5}\right)^{2/3}G\cdot d\cdot (3_~V)^{1/3}\]

For comparison, we place the Little Prince on a spherical planet with the same volume, density and radius \(_~R_~\). \(~r^2~\) then runs in the interval \(_~[_~0,~{R^2-(R-z)^2}_~]~=~[_~0,~{2_~R_~z_~-_~z^2}_~]\).

\[F_{z~sphere}~=~G\cdot d\cdot \int_{0}^{2_~R}\int_{0}^{\sqrt{2_~R_~z_~-_~z^2}}\int_{0}^{2_~\pi} \frac{z\cdot r}{(r^2+z^2)^{~3/2}}~d\phi~dr~dz\]

\[~~~~~~=~2\cdot \pi\cdot G\cdot d\cdot \int_{0}^{2_~R} \left[_~-\frac{z}{\sqrt{r^2+z^2}}~\right]_{r~=~0}^{r~=~\sqrt{2_~R_~z_~-_~z^2}}~dz\]

\[~~~~~~=~2\cdot \pi\cdot G\cdot d\cdot \int_{0}^{2_~R} \left(1-\sqrt{\frac{z}{2_~R}}~\right)~dz\]

\[~~~~~~=~2\cdot \pi\cdot G\cdot d\cdot \left[_~z-\frac{2}{3}\cdot \frac{z^{3/2}}{\sqrt{2_~R}}_~\right]_{0}^{2_~R}~=~\frac{4}{3}\cdot \pi\cdot G\cdot d\cdot R\]

With \(_~R=(3V/(4\pi))^{1/3}\) we get

\[\textbf{(8)}~~~~F_{z~sphere}=\left(\frac{4_~\pi}{3}\right)^{2/3}G\cdot d\cdot V^{1/3}\]

The comparison of (7) and (8) gives \(F_{z}/F_{z~sphere}\approx 1,026_~\); for the exact value look at the summary below.

For completeness, we want to show that the gravitational force in \(_~x-_~\) and \(_~y-\)direction is \(_~=0_~\). In cylinder coordinates is \(~x=r\cdot cos~\phi,~~y=r\cdot sin~\phi_~\). For the prince's planet as well for the spherical planet, the following equations hold:

\[F~_{x \atop y}=G\cdot d\cdot \int_{0}^{..} \int_{0}^{..} \int_{0}^{2_~\pi} \frac{r^2~{cos~\phi \atop sin~\phi}}{\sqrt{r^2+z^2}}~d\phi~dr~dz~=~G\cdot d\cdot \int_{0}^{..} \int_{0}^{..} \frac{r^2}{\sqrt{r^2+z^2}} \int_{0}^{2_~\pi} {cos~\phi \atop sin~\phi}~d\phi~dr~dz~=~G\cdot d\cdot \int_{0}^{..} \int_{0}^{..} \frac{r^2}{\sqrt{r^2+z^2}}\cdot 0~dr~dz~=~0\]

|

Summary

A planet with volume \(~V~\) and homogeneous density \(~d~\) is placed into a Cartesian \(_~(x,y,z)-\)coordinate system such that a surface point lies at \(_~(0,0,0)_~\). The shape of the planet is to be chosen so that the gravitational attraction in the positive \(_~z-\)direction at this point is maximized. The solution results in a rotational solid with the \(_~z-\)axis as the axis of rotation. The generating curve gives the radius \(~r~\) in the cross-section plane at height \(~z_~\): \[r(z)=\sqrt{C\cdot z^{2/3}-z^{2~}}\] The key step in the proof for this solution is showing that the gravitational attraction on the planet's surface is constant. The planet then lies entirely in the positive \(_~z-\)half-space and has no voids. Its shape does not depend on the constant \(~C_~\), so all planets with any given \(~C~\) are geometrically similar. \(~C~\) is calculated as a function of \(~V_~\): \[C=\left(\frac{15_~V}{4_~\pi}\right)^{4/9}\] The required maximum gravitational pull is \[F_z=\left(\frac{3}{25}\right)^{1/3}\cdot \left(4_~\pi\right)^{2/3}\cdot G\cdot d\cdot V^{1/3}~\approx~2,6660\cdot G\cdot d\cdot V^{1/3}\] \(~G~\) gravitational constant A comparison with a spherical planet of the same volume and density gives \[F_{z~sphere}=\left(\frac{1}{9}\right)^{1/3}\cdot \left(4_~\pi\right)^{2/3}\cdot G\cdot d\cdot V^{1/3}~\approx~2,5985\cdot G\cdot d\cdot V^{1/3}\] \[\frac{F_z}{F_{z~sphere}} = \frac{3}{5^{2/3}}~\approx~1,026\] The gravitational acceleration in \(_~(0,0,0)_~\) derived from the optimal shape is about \(2,6_~\%_~\) higher than that of a sphere. |

Example

Here, the physical units will also be included.

For the Earth (assumed to be spherical with constant density) and the rotational solid described above, we set

\[V\approx 1,0833\cdot 10^{21}~m^3,~~~~d\approx 5,517\cdot 10^3~\frac{kg}{m^3},~~~~G\approx 6,6743\cdot 10^{-11}~\frac{N\cdot m^2}{kg^2}\]

\[\Longrightarrow~~~F_z\approx 10,082~\frac{N}{kg}=10,082~\frac{m}{s^2}~,~~~~~F_{z~sphere}\approx 9,827~\frac{N}{kg}=9,827~\frac{m}{s^2}\]

In economics we find an analogous problem: the Equimarginal Principle.

This principle was formulated by Hermann Heinrich Gossen in 1854 and can be classified as an economic axiom. The equimarginal principle describes how resources must be used to achieve maximum yield. With our Little Prince, the point masses of the planet correspond to resources, and the gravitational effect corresponds to yield.

Explanations of the equimarginal principle can be found on Economics online.

Last update 2025-07-06 Comments are welcome.

blog overview | previous article